Circadian rhythm, vitamin D, recovery, and why response differs between people

In physics terms, light is energy and information, delivered to the body in precise packets called photons. These smallest of particles are capable of entering the body and triggering chemical reactions that influence sleep, immunity, recovery, and long-term health.

As Industry hints at, interest in this topic has grown partly through researchers and communicators such as Andrew Huberman, who has highlighted the importance of morning light exposure for circadian health, and through discussions with clinicians like Dr Roger Seheult, who references frameworks such as NEWSTART, where sunlight is treated as a foundational health input.

The episode between Huberman and Seheult is a good listen. In it, they emphasise that sunlight supports health primarily through circadian regulation and vitamin D biology rather than vague energy effects. Funnily enough, it was also the first time I properly connected the dots between light physically entering the body and triggering a real chemical response.

So let’s roll up our sleeves and look at three types of light and how they actually affect the body.

What is light?

Light is a form of electromagnetic radiation. At the smallest scale, it exists as packets of energy called photons. Photons are produced in the sun through nuclear fusion. During this intensely energetic process, photons are created with a wide range of energies, some extremely high, some a bit less.

Travelling at the speed of light, these photons cover the distance between the sun and the Earth in about eight minutes and then get to work on planet Earth.

-

Shorter wavelengths carry more energy, such as ultraviolet light.

-

Longer wavelengths carry less energy, such as infrared light.

Although all photons are fundamentally the same particle, wavelength determines how deeply light can penetrate tissue and which molecules it interacts with once absorbed.

Why wavelength matters: penetration and effect

When light reaches the body, photons are either reflected, transmitted, or absorbed. Biological effects occur only when photons are absorbed.

-

Short, high-energy wavelengths such as UVB are absorbed quickly near the skin surface and trigger chemical reactions. Think sunburn.

-

Longer wavelengths such as red and near-infrared interact more gently, allowing them to penetrate deeper into tissue before being absorbed. Think infrared sauna.

This distinction explains why UVB is involved in vitamin D synthesis, while infrared light is discussed in the context of local tissue recovery.

Morning light and circadian rhythm

Visible light, particularly in the morning, plays a central role in regulating the circadian rhythm, which is the body’s internal clock.

In the early part of the day, sunlight contains a higher proportion of shorter-wavelength, blue-enriched light due to the sun’s angle in the sky. The eye responds to this spectral composition, not just overall brightness.

Specialised retinal cells, separate from those used for vision, detect this light and send signals directly to the brain’s master clock. This triggers a healthy rise in cortisol in the morning, helping wake the body and mobilise energy. Crucially, it also starts a biological timer.

Roughly 14 to 16 hours later, that same clock allows melatonin to rise, provided light exposure is low. In simple terms, morning light does not just help you wake up. It helps determine when you feel sleepy later that night.

A review of human circadian biology shows that morning light exposure shifts the circadian clock earlier and improves sleep timing, while light exposure in the evening or at night shifts the clock later and disrupts sleep and recovery.

Put simply, when you get light matters just as much as how much light you get.

This matters because sleep is when immune repair is prioritised, protein synthesis increases, and tissue regeneration accelerates.

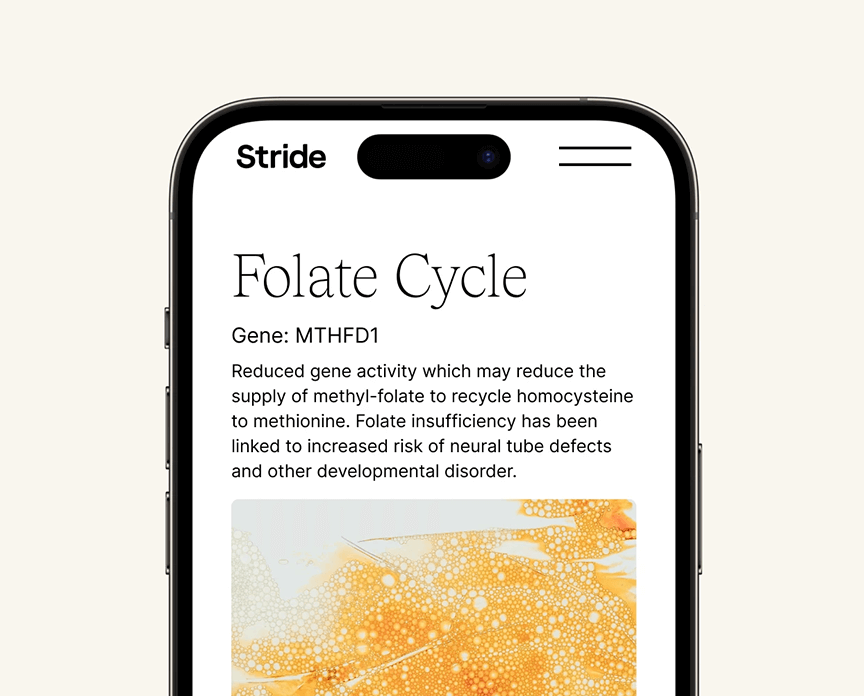

Genetics adds another layer of context here. Circadian rhythm is shaped by a network of genes, including PER2 and PER3, which influence whether someone naturally leans more towards being a morning person or a night owl. My own Stride results sit slightly towards the evening end of that spectrum. There is nothing pathological about that, but it does mean my internal clock is more comfortable running later than a conventional early-morning schedule.

In practical terms, this gives morning sunlight more leverage for me than it might have for someone with a stronger morning-leaning profile. Bright light early in the day helps pull my body clock forward, reinforcing an earlier cortisol rise and setting up melatonin release later that night. Without deliberately anchoring my day this way, it would be very easy for my natural tendency to drift later and later, especially when work is engaging or cognitively demanding. Morning light acts as a simple, non-negotiable cue that keeps my rhythm aligned with modern work and social schedules.

UVB light, vitamin D, and seasonality

Sunlight boosts vitamin D production

We have all heard that you need sunlight to create vitamin D. But how?

Vitamin D is what is known as a photochemical product, meaning it is made through a chemical reaction triggered by light.

UVB from the sun penetrates the outer layers of the skin, typically reaching the epidermis rather than deep tissues. When UVB light in the 280 to 315 nm range strikes a cholesterol-derived molecule in skin cells called 7-dehydrocholesterol, it triggers a direct chemical reaction that converts it into pre-vitamin D3.

This molecule is then transformed by heat in the skin into vitamin D3, also known as cholecalciferol. From there, it enters the bloodstream and is further processed by the liver and kidneys into its active, hormone-like form.

Once activated, vitamin D influences immune regulation, inflammation, muscle function, and bone health.

Why seasonality matters in the UK

Research examining UVB availability at UK latitudes shows that from roughly October to March, the sun’s angle is too low for meaningful UVB to reach the ground, making vitamin D synthesis from sunlight effectively negligible during winter months.

In simple terms, during the UK winter, sunlight does not contain enough UVB to trigger vitamin D production in the skin, regardless of how much time you spend outdoors.

Even in the summer months, vitamin D production depends on sufficient skin exposure. UVB must directly reach the skin, meaning exposed areas such as arms and legs are far more effective than small areas like the face and hands. Clothing, sunscreen, and limited surface area can significantly reduce vitamin D synthesis, even when UVB is present.

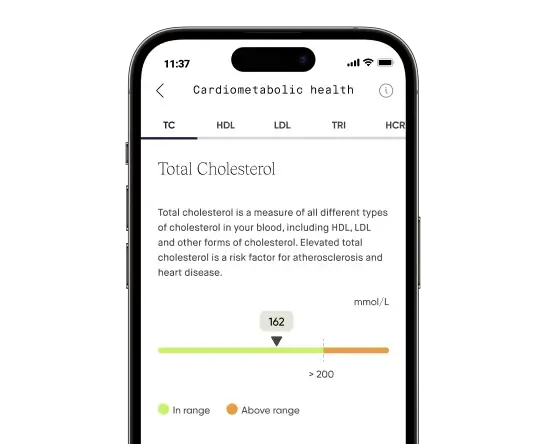

This helps explain why vitamin D insufficiency is common in winter, and why some people remain insufficient year-round despite spending time outdoors. It also highlights why blood testing is more reliable than assumptions based on lifestyle alone.

Genetics and vitamin D signalling: the VDR gene

Vitamin D only exerts its effects once it binds to the vitamin D receptor, known as VDR, inside cells. Genetic variation in the VDR gene influences how efficiently vitamin D signalling occurs.

This means two people with the same vitamin D level can experience different biological effects, and some individuals require higher or more consistent vitamin D levels to achieve the same outcome.

My own blood tests via StrideOne show a vitamin D level that sits comfortably in the sufficient range. On paper, that looks fine. However, my DNA results show an AG variant in the VDR gene, which is associated with slightly less efficient vitamin D signalling.

In practical terms, that means that even with a reasonable blood level, I may need a little more consistency from sunlight or supplementation to achieve the same biological effect as someone with more efficient signalling. This is not about being deficient. It is about understanding demand as well as supply.

A DNA and methylation test like Stride does not replace blood testing, but it helps explain why vitamin D needs differ between individuals and why normal does not always mean optimal for everyone.

Infrared light, recovery, and tissue repair

Red and near-infrared light interact with the body in a fundamentally different way from UV light. Rather than triggering hormone production, they act locally within tissues, interacting with cellular systems involved in energy production, oxidative stress, and inflammatory signalling.

This is the same principle behind some physiotherapy tools. I have personally had a low-level laser used during a physio session to treat IT band issues. It was a small, pen-like device applied very locally to irritated tissue as part of a broader rehabilitation approach.

A widely cited mechanistic review of photobiomodulation shows that red and near-infrared light can influence cellular signalling pathways linked to inflammation and tissue repair, primarily through effects on mitochondrial function and oxidative stress balance. The strongest and most consistent evidence is seen in local applications rather than whole-body effects.

Systematic reviews of clinical studies suggest that near-infrared light can improve certain wound-healing outcomes, particularly in controlled clinical or rehabilitation settings. These effects appear to be local and highly dependent on factors such as dose, wavelength, tissue type, and treatment context.

What about consumer red-light panels?

Off the back of this research, it is no surprise that consumer red and near-infrared light panels have entered the market. These devices aim to deliver specific wavelengths of light associated with cellular energy production, oxidative stress, and inflammatory signalling, similar in principle to tools used in physiotherapy and rehabilitation. In theory, they are designed to support local tissue recovery rather than whole-body effects.

That said, there are important caveats. Dose, wavelength, distance, and exposure time all matter, and consumer devices vary widely in how much biologically meaningful light they actually deliver. Any effects are likely to be local rather than systemic and are best thought of as a complement to sleep, training management, and nutrition rather than a shortcut or replacement. Used with realistic expectations, they may offer modest support for specific areas, but they are not a substitute for sunlight, recovery, or personalised health insight.

Light as a biological input, not a wellness trend

The benefits of light are real. Light influences health through distinct mechanisms.

-

Visible light anchors circadian rhythm and sleep timing.

-

UVB light enables vitamin D synthesis, constrained by season and latitude.

-

Infrared light interacts locally with cellular recovery pathways.

Each wavelength carries different amounts of energy, penetrates tissue differently, and targets different biological systems.

This is why no single light exposure does everything, and why you need to consider factors such as what you are wearing, the time of year, and even your genetics in order to maximise the benefits of light exposure.

Understanding how light works allows you to make informed, personalised decisions rather than relying on generic advice.

FAQs

1. Does morning sunlight really improve sleep?

Yes. Morning light helps set your circadian clock earlier, which supports a healthy cortisol rise in the morning and allows melatonin to rise at night, improving sleep timing and quality.

2. Can I get vitamin D from sunlight in the UK winter?

For most people, no. From roughly October to March, UK sunlight contains too little UVB to trigger meaningful vitamin D production in the skin.

3. Is vitamin D production affected by clothing?

Yes. UVB must directly reach the skin. Exposed areas such as arms and legs are far more effective than small areas like the face and hands.

4. Why do two people respond differently to vitamin D?

Genetic differences, particularly in the vitamin D receptor gene, influence how efficiently vitamin D signalling occurs inside cells.

5. Does infrared light boost immunity?

There is no strong evidence that infrared light boosts whole-body immunity. Its effects appear to be local and related to tissue recovery and inflammation.

6. Are consumer red-light panels worth using?

They may offer modest benefits for local recovery when used appropriately, but effects depend on dose, wavelength, and context. They are not a replacement for sleep, nutrition, or sunlight.

7. Is light really that important for health?

Yes. Light is a foundational biological input that influences sleep, hormone timing, vitamin D production, and recovery. Modern lifestyles often disrupt natural light exposure, making conscious management increasingly relevant.