A lot of us may have heard the term Dry January being thrown around this month. Some may have tried it as a challenge, others maybe as a punishment for December over-indulgence. For many, it’s something they may try for a couple of weeks, then quietly abandon.

Why Dry January became a thing

Dry January began as a public-health initiative, but it quickly became a cultural trend. January naturally lends itself to behaviour change as it’s the start of a fresh, new year. Often, motivation to change, start the year strong, or have a “reset” is high. In the Northern Hemisphere, it is also usually socially quieter after the festive period, so it may be a convenient time to intentionally take a break from alcohol.

More recently, Dry January has been joined by similar sober-curious movements: Sober October, No Beer for a Year, 75-Hard, and 1,000 Days Sober. What these trends reflect is a growing curiosity about the negative effects of alcohol on overall health. This is especially true for people who pay close attention to optimising their nutrition and exercise, but feel they are being held back by their alcohol habits in social situations.

In this case, going “dry” for January can also reduce social pressure around drinking. When a friend asks, “Why don’t you have a drink?”, it’s often easier to respond with “I’m doing Dry January this month” and be met with understanding rather than needing to justify yourself.

The benefits of stopping alcohol for one month can be significant, and in many cases continue even when alcohol is reintroduced.

Alcohol through a health-optimisation lens

Alcohol is unique metabolically. Unlike carbohydrates, fats, or protein, alcohol cannot be stored. When consumed, the body treats alcohol as a toxin and prioritises its metabolism over other fuels. This means that while alcohol is being processed in the liver, many other physiological processes are temporarily put on hold — a phenomenon well described in scientific reviews of alcohol metabolism pathways.

This can have a wide range of negative health effects associated with alcohol intake, even at relatively moderate levels of consumption. For example:

Sleep quality

Alcohol may help you fall asleep faster, but it disrupts REM sleep and increases night-time awakenings. It also worsens sleep-disordered breathing and reduces melatonin production, which leads to lighter, less restorative sleep overall. The result is poorer recovery and next-day fatigue, even when total sleep time appears unchanged. This effect — where alcohol disrupts the architecture of sleep — has been reported in research showing how alcohol can disrupt normal sleep patterns and reduce sleep quality.

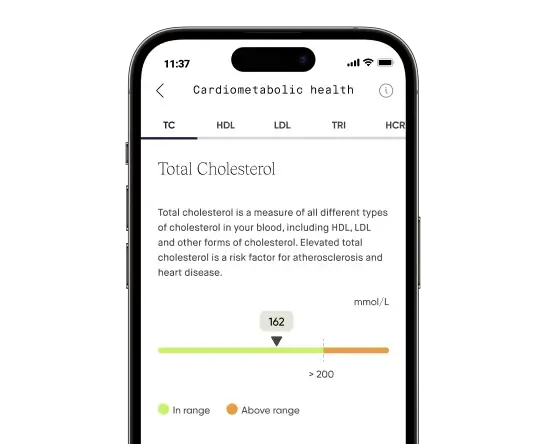

Impaired metabolic health and blood sugar control

Alcohol intake disrupts blood-sugar regulation, making the body more sensitive to refined carbohydrates and contributing to energy spikes and dips. Over time, this can promote visceral fat accumulation and elevate the risk of insulin resistance and other metabolic health issues.

Gut barrier integrity

Alcohol can irritate the gut lining and alter the gut microbiome. This can lead to bloating, uncomfortable digestion, and irregular bowel movements. With repeated use, alcohol can increase intestinal permeability — often referred to as “leaky gut.” Excessive alcohol use has been linked to changes in the gut microbiome and impaired gut epithelial function, which may contribute to systemic inflammation and nutrient malabsorption (gut microbiome & barrier review).

Inflammation

As alcohol is metabolised it produces acetaldehyde, a toxic compound that generates reactive oxygen species and activates inflammatory pathways such as NF-κB. Alcohol can also increase gut permeability, allowing bacterial endotoxins into circulation, triggering systemic immune activation and pro-inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-6. Over time, these processes contribute to chronic low-grade inflammation and may worsen inflammatory conditions affecting the gut, joints, skin, and brain.

Nutrient deficiencies

Alcohol impairs nutrient absorption in the gut, decreasing uptake of folate (B9), magnesium, zinc, calcium, and iron, while also increasing urinary loss of minerals like magnesium and potassium. Alcohol metabolism places high demand on liver detoxification pathways, accelerating depletion of B vitamins (particularly B1, B6, folate, and B12) and antioxidants such as glutathione. Over time, these effects can contribute to fatigue, impaired neurological function, weakened immunity, poor skin health, and disrupted energy metabolism.

Increased resting heart rate

Alcohol stimulates the sympathetic nervous system, elevating resting heart rate. Its metabolism raises catecholamine release, increases cortisol, and promotes dehydration and electrolyte imbalance, all of which place strain on the cardiovascular system. Because alcohol also disrupts sleep, it prevents the normal night-time drop in heart rate. Over time, regular intake can result in a higher baseline resting heart rate, reduced heart-rate variability, and increased cardiovascular stress.

Mood disturbances

Alcohol can negatively affect mood by disrupting neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine. It increases oxidative stress, reducing availability of BH4, a critical cofactor required for neurotransmitter production. In people with genetic variation affecting BH4 pathways, this effect can be more pronounced, increasing sensitivity to anxiety or low mood after drinking. Combined with alcohol’s impact on sleep and stress hormones, this can contribute to emotional instability with regular use.

Integrating Dry January habits into everyday life

Dry January isn’t about perfection or moralising alcohol consumption. For some, it acts as a reset. For others, it provides clarity on how alcohol fits (or doesn’t fit) into their lifestyle. Even reducing intake, rather than completely eliminating it, can produce meaningful health benefits.

Ultimately, it’s about finding an approach that supports health optimisation in a sustainable way. It doesn’t have to be all-or-nothing. For many people, this may mean continuing to include alcohol occasionally, but in more controlled amounts, informed by a better understanding of its effects on the body.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Does Dry January actually improve health?

For many people, even a month without alcohol can improve sleep quality, energy levels, digestion, and mood. Observational research shows that those who participate in Dry January report measurable benefits in these areas, including improvements in liver function and blood pressure.

How does alcohol affect sleep quality?

Alcohol may seem to help with falling asleep, but it reduces REM sleep and increases night-time awakenings, meaning sleep is less restorative. Disrupted sleep is one of the most common complaints associated with alcohol intake.

Is alcohol really treated as a toxin by the body?

Yes. Unlike carbohydrates, fats, or protein, alcohol cannot be stored and is prioritised for metabolism in the liver. This means other metabolic processes are temporarily paused while alcohol is cleared, which can have downstream effects on energy usage and recovery.

Can taking a break from alcohol reduce inflammation?

Alcohol metabolism produces acetaldehyde and other compounds that activate inflammatory pathways. Reducing alcohol intake can lower systemic inflammation over time, which may benefit gut health, joint comfort, and overall immune function.

Do the benefits of Dry January last after alcohol is reintroduced?

Often, yes. Many people find that after a period of abstinence, they naturally drink less, sleep better, and are more aware of how alcohol affects their bodies. Even a sustained reduction in intake, rather than complete avoidance, can preserve many of the initial benefits.